Social isolation can transform a mouse’s brain. Among other behaviours, mice kept alone for two weeks become hypersensitive to a threat, freezing, and staying that way, long after the threat is over.

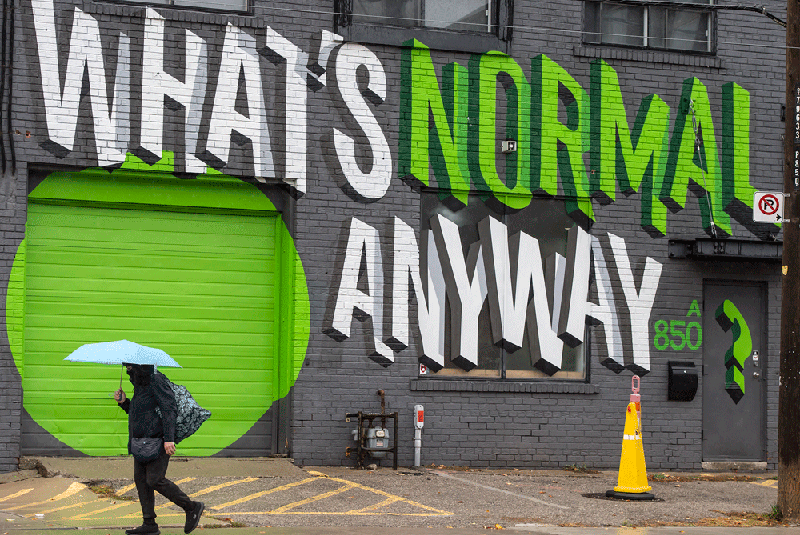

A flurry of surveys this week would suggest we’re all becoming similarly unhinged by COVID-19 social isolation. Taken together, the polls — from Toronto’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), Angus Reid Institute and human resources firm Morneau Shepell — paint a worrisome picture of strained emotions as we hit the pandemic’s seven-month mark. But how much of what people are experiencing are perfectly normal, human reactions to an entirely abnormal situation?

According to CAMH’s ongoing national survey, conducted in collaboration with Delvinia, women (24 per cent) are experiencing higher levels of anxiety than men (18 per cent), parents with children under 18 living at home are more likely to say they’re feeling depressed (29 per cent) compared to adults without kids in this age group (19 per cent). One-quarter of both men and women worry about getting COVID-19, while a worrying 29 per cent of men and 23 per cent of women are engaging in heavy episodic drinking in social isolation.

More than 200 days in, we’re emotionally exhausted, according to Morneau Shepell’s latest report from its mental health index, based on an online survey of 3,000 people in late August, before the second surge. We’re less motivated at work. We’re struggling to concentrate. Worries over job security and dwindling emergency savings, and juggling multiple “mental and situational distractions, on top of the work,” is draining, Morneau Shepell’s Paula Allen, senior vice president of research, analytics and innovation, said in a release.

From Angus Reid comes the finding that the percentage of Canadians who could be categorized as “The Desolate” — those suffering from both loneliness and social isolation — has increased from 23 per cent of the population last year, to 33 per cent. Our interactions with nearly every social group have diminished. Even over the summer, despite the reopened patios and beaches and the chance to expand our bubbles, “most made an effort to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 by avoiding personal contact with others,” the pollster found. For many, there is far too much time alone; for others there is no alone time, and they would appreciate more of it.

- – Tips for managing mental health during COVID-19

- – Michael Lochran: The coming mental health storm

- – Potential explosion in mental illness could last years after pandemic: study

While women are more likely to admit to problems like anxiety, “my suspicion is there are more men who are anxious but they chose not to say so,” says CAMH psychiatrist Dr. David Gratzer. And while we’re finding different ways of coping with the pandemic in social isolation, the choice of alcohol, Gratzer says, is “deeply problematic and could haunt people in the future.”

These are uncertain times, and it’s unsurprising that people would be stressed out, Gratzer says. One of his patients won’t leave his home unless absolutely necessary. “One can understand where he’s coming from — there’s virus in the community. It’s spread by contact with others.” Some people are more vulnerable in times of stress, and they are the ones we should be most worried about. Gratzer thinks of the person he saw in the emergency department a few weeks ago — someone with a history of anxiety disorder, but who is normally highly functional. “He’s gone from somebody with a lot of anxiety who can cope, to somebody who calls in sick regularly and is having difficulty coping. He needs access to care. He needs evidence-based interventions.”

The pandemic, the strain of job loss, the days spent in social isolation confined to their homes, the lost physical connections with family and friends — all of it has made people who never before had mental illness experience symptoms of anxiety and depression, and made people with mental illness “sicker than they were,” Andrew Solomon, writer, lecturer and professor of clinical psychology at Columbia University said this week on The Quarantine Tapes, a program from Onassis LA and dublab, a non-profit internet radio station. “And it’s even left the people who don’t trend into the territory of clinical diagnosis with a sense of impermanence and fragility that I think there is no comparison for,” said Solomon, author of The Noonday Demon: An Atlas of Depression.

The pandemic “has given us a sense that there can be something not which is immediate and horrifying, like 9/11 or like an earthquake, but something that is sustained and completely changes the way that we interact and socialize with one another,” Solomon told host Paul Holdengraber.

We’re struggling between being uber-cautious and under-cautious, Solomon said, “and we have to balance all the time the sense of the terrible physical risk that’s attached to seeing people, and the sense of mental or psychological risk that’s attached to not seeing people. And I think that’s especially acute for children.”

People were less anxious in the summer months, and now, with confirmed COVID-19 cases creeping up, to be blunt, “more COVID, more problems,” Gratzer says. At CAMH, emergency room visits are back to pre-pandemic levels after a dramatic fall off in the first wave.

Frontline workers — nurses, doctors, personal support workers, first responders, retail clerks — have been exposed to serious and often unrelenting stress, according to a policy briefing published this week by a Royal Society of Canada working group. People who have experienced symptoms anxiously await tests. Some have been hospitalized, some have been put on ventilators and more than 9,700 Canadians have died. We’ve heard endless health warnings, and the daily case counts are becoming mind-numbing. About 20 to 25 per cent of Canadians, depending on the survey, are experiencing “moderate or severe COVID-19-related mental health problems,” according to the briefing paper. Those living in poverty, some racialized and Indigenous groups, and those with pre-existing mental health problems are suffering the most.

Some people are more vulnerable in times of stress, and they are the ones we should be most worried about.

Pandemics are dynamic events, changing over time, “and so too has the stress experienced by people,” says Dr. Gordon Asmundson, a professor of psychology at the University of Regina and one of the authors of the Royal Society paper. “Until we have a better understanding of this virus, its behaviour and a vaccine, many people are going to experience stress.” About 15 per cent may not adapt, and become “functionally impaired” as a consequence of COVID-related stress, he says. “The psychological footprint of the pandemic is likely as big, if not bigger, than the medical footprint.”

Yet Canada’s mental health system was stretched even before the pandemic. “We need to get our game up,” Gratzer says. Among its recommendations, The Royal Society paper is urging the federal government to increase funding for mental health to at least 12 per cent of the health services budget, and national standards established for quality mental health care under a Mental Health Parity Act.

Fear, sadness, grief, loneliness, frustration, irritability — all are normal responses to the pandemic, says eminent psychiatrist Dr. Allen Frances, a professor emeritus and former chair of the department of psychiatry at Duke University. “The increased rates of painful emotions in the general population do not necessarily mean an increase in rates of clinical mental disorder,” says Frances. He isn’t minimizing people’s feelings. Instead, it’s important that people realize they aren’t in this alone, that it’s likely to be time-limited, “and it doesn’t mean you’re going to have a chronic mental illness.”

Psychotherapy, now more accessible than ever via virtual care, can help people cope with abnormal stressors, Frances says. What he doesn’t support is a huge increase in antidepressant use. “I think we have to normalize this as the new normal — the idea that we’re going to face tremendous stressors from repeated pandemics, and even more from climate change,” Frances says.

It’s unlikely any magic bullet will suddenly end the pandemic. “And so people have to start thinking long-term, not waiting, ‘oh, I’ll be OK’ or the world will be OK next month, or even next year,” Frances says. “People have to start planning their next several years in a way that doesn’t have them constantly anxious and sad and regretting what’s been lost, but rather finds the most in each day under these new circumstances.”

How do we adjust our lives so that they are satisfying, despite this being a chronic stress? “Find things you enjoy the most, and fill your day with as many good minutes as possible,” Frances says. “Find the people who matter the most to you and the things that matter the most to you.” Exercise, even a brisk walk, listening to music, reaching out to people via social networking — “the things that make life worth living, most of them can be preserved even in the midst of a pandemic.”

But humans are remarkably resilient. ”This is terrible, but it’s not as bad as being in the Blitz in London,” Frances says. It’s also rational to be cautious of others. Even with herd immunity achieved via vaccination, the virus will still spread, though more slowly. “So a rational person should be cautious and fearful for probably the next several years, especially if they are in high-risk groups,” says Frances.

Gratzer recommends people reach out to a family doctor and begin a conversation if what they’re feeling goes beyond feeling stressed. The CAMH site has information on coping strategies for COVID anxiety, as well as how to talk to children about the pandemic virus.

Read the full article on SaltWire.com.